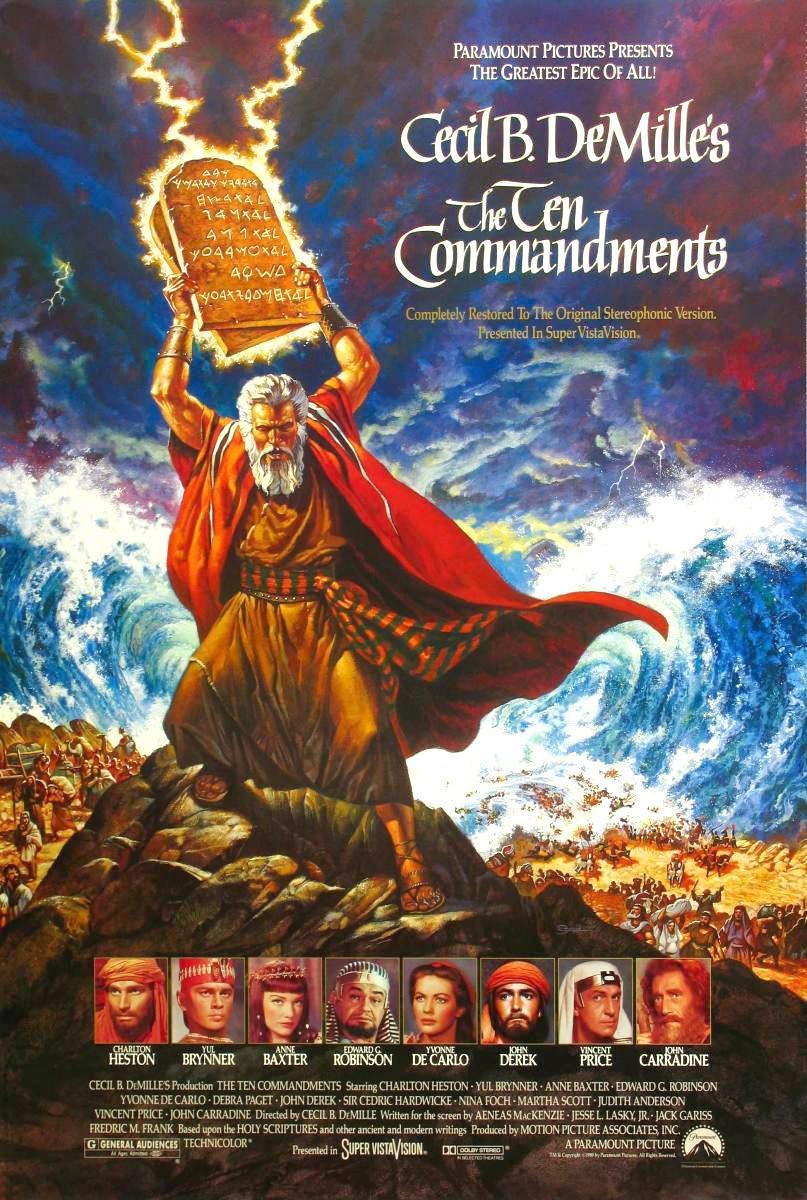

“Those who see this motion picture—produced and directed by Cecil B. DeMille,” opens the text crawl of DeMille’s The Ten Commandments(1956) at the end of its sweeping five minute opening credits, “will make a pilgrimage over the very ground that Moses trod more than 3,000 years ago—in accordance with the ancient texts of Philo, Josephus, Eusebius, The Midrash, and,” the credits finish with a visual flourish, “The Holy Scripture.”

A boast if there ever was one, and hardly wasted on DeMille’s masterwork. The Ten Commandments remains the sixth highest-grossing film of all time after adjusting for inflation, seen by hundreds of millions of people, and still running on American cable every year, either leading up to Christmas or Easter. Yet, the majority of Americans today can’t actually list the Ten Commandments, and fewer have a strong understanding of the Exodus narrative as found in the Bible, let alone ancient Mosaic tradition. With secularism waxing and popular religious understanding waning, what is the use of such a film? Is it irrelevant? A reader may find the opposite, that DeMille’s work is increasingly relevant, if less in itself and more in the movement it exemplifies.

In citing Philo, Josephus and Eusebius, DeMille pays his respects to those early scholars and apologists, whose writings on religion, whether from the Jewish or Christian side, remain influential today. However, citing the Jewish Midrash is more problematic, not in the least because the Midrash is not a single text, but a category of writing around canonical religious works. Even by the strictest definitions, midrashim include all rabbinical writings surrounding the Tanakh, which hardly makes for a concise or coherent source.

Luckily, Henry Noerdlinger, DeMille’s researcher for the film, compiled his research into a book, Moses and Egypt. While much of it covers technical material, such as the particulars of Egyptian jewelry or Hebrew costuming, the beginning of the book describes exhaustively the sources used by DeMille and the decisions made in adapting both scripture and supplemental materials into the film. Here we find exactly what DeMille was citing, Philo’s On the Life of Moses, Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities and Eusebius’ Preparation for the Gospel. We also find that the midrashic influence came from the Midrash Rabbah, which for DeMille’s purposes, was limited to the Exodus Rabbah. The Exodus Rabbah is an entirely haggadic text, meaning it focuses on moral lessons gleaned from stories (Haggadah, or הגדה, roughly translates as ‘fairy tale’) as opposed to rigorous interrogation of the text to understand its legal components. This haggadic approach, we will see, defines the presentation of the film as a whole.

While the early life of Moses, which comprises the bulk of the film, is not of Scriptural origin, it has strong sources outside of modern historical novels. While both the Tanakh and Quran imply that Moses was a prince of Egypt through his adoption into the royal family, Philo and Josephus wrote extensively on the subject. Far from being a modern invention, there appears to have been an extensive Mosaic tradition regarding his time at the Egyptian court. DeMille is hardly guilty, as some might suppose, of fabricating Moses’ early life for the sake of drama; if anything, The Ten Commandments cuts most of it out.

|

| That schmuck DeMille cut out the best part! |

Large chapters of Philo and Josephus’ accounts of Moses tell not only of court intrigue in Egypt, but of adventures often de-emphasized in mainstream portrayals of Moses’ life. In particular, they wrote about Moses’ time leading the Egyptian armies against Ethiopia, succeeding in conquering them. Moses as a conqueror and general of Egypt isn’t often how he is seen; it’s hard to imagine the white-bearded prophet charging into battle. This character, nevertheless, does appear in The Ten Commandments. Moses’ first appearance as an adult is in full armor, come from conquering the Ethiopians. This seems at odds to the modern understanding of Moses. Though the Israelites do go to war while he leads them, he always delegates battle to another, never directly participating in combat from that point onward.

Further, while both the Exodus narrative and The Ten Commandments show Moses fleeing straight to Midian after being chased from Egypt, the ancients had an altogether different understanding. While Moses and Egypt does not mention it, both Josephus and the wider Rabbinical literature peg Moses not in Midian, but in Ethiopia immediately after his escape, where he is once again at the head of an army, recovering the Ethiopians’ capital from Balaam, who was then a servant of the Pharaoh. According to Josephus, Moses remains in Ethiopia, being crowned as a king there and marrying the Ethiopian queen, Adoniya.

He then goes on to rule the Ethiopians for a full forty years (like the forty years wandering through the desert, a common biblical shorthand for ‘a long time’). However, he refuses to have a child or cohabitate with his new wife, and is eventually dismissed by the Ethiopians. In Josephus’ account, Moses escapes Egypt at age 18, spends nine years with the army, then forty as a king, making him 67 years old when he finally arrives at Midian. The Exodus narrative as it is commonly known continues from there. Even more curiously, that section of Josephus isn’t so much as mentioned in Moses and Egypt, indicating that Noerdlinger didn’t consider it relevant to mention, as he must have read it in his research.

It’s understandable why DeMille might cut this section of Moses’ story from his films. Beyond not being in the scripture, it screws up the pacing somewhat. It already takes three hours to get to the big attractions of the film, parting the Red Sea and receiving the Decalogue, and I don’t think anybody wants a nine-hour director’s cut. That said, selectively borrowing from traditional sources does create a warped public perception of the Exodus narrative, especially coming from the most influential piece of media that depicts it.

The result is neither a purely Tanakhic or Quranic depiction of Moses, nor one that adheres to rabbinical or traditional accounts, but a distinct, transformed image of Moses. A Moses for modernity, an updated lawgiver for a new era. Central to this new Moses is a focus on the man instead of the Law; not only is the personal journey filed down and scrubbed of aesthetically unpleasant episodes, so too is the Law de-emphasized in order that the man can be appreciated by people of all faiths and creeds. It is the conversion of Moses from an inherently Jewish prophet to a non-sectarian legend that current-day leaders can be readily compared to; a clean, inspirational, nearly secular myth for America to crowd around the TV and identify with.

Judaism being, fundamentally, a religion of laws, the presentation of law in the Ten Commandments is a key feature around which the film may be judged. As the reader may guess, it does not faithfully cleave to the Talmudic division, but more importantly, the film keeps mum on any laws beside its blockbuster draw.

The Decalogue as depicted in the film conforms strongly to the Philonic division, used today most prominently by Protestant Christians. The very first commandment reads simply, “You shall have no other gods before me.” Most Jews, drawing on the Talmudic division, place the first commandment as “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of Egypt,” or some variation on that phrasing, and groups “You shall have no other gods before me,” with “You shall make no graven images,” as the second. Meanwhile, the Catholic division, expressed in the traditional catechetical formula, brings the Talmudic first and second commandments together while removing any mention of graven idols; instead, the Catholic Second Commandment is “Do not take the LORD’S name in vain,” and the Third Commandment is to, “Keep holy the LORD’S day,” respectively the Third and Fourth Commandment in other divisions. This missing commandment is made up by splitting the coveting passage into two, the Ninth regarding the neighbor’s wife, the Tenth regarding the neighbor’s property. The Decalogue shown in the film, on the other hand, keeps the Talmudic first and second commandments separate, and generalizes the tenth to “Thou shalt not covet anything that is thy neighbor’s,” providing a concise and punchy summary of Philo’s Decalogue.

In this way, it is clear that DeMille’s own Protestant convictions formed the basis for his depiction of the Decalogue. Besides his inclusion of graven images (especially useful given what the Israelites were doing at the time Moses received the commandments), his translation of the Sixth Commandment as “Thou shalt not kill,” as opposed to “Thou shalt not murder,” cements it in the modern Christian tradition as opposed to the Jewish understanding.

Concerningly for scholars of Mosaic law in the audience, the laws following the Decalogue are cut from the film with nary a mention. The intricate code of property rights, tabernacle construction ordinances and regulations surrounding priestly garb which is contained in Exodus 20:22-31:18 is, tragically, not explored with a further half-hour of intense note-taking by Moses. The film speeds instead to the construction of the Golden Calf and the destruction of the original tablets, full of drama and several minutes of gratuitous, Technicolor-enabled lasciviousness by the Israelites.

|

| Shake what Baal gave you baby! |

From there, the film skips straight to the events of Deuteronomy 34, in which Moses looks upon the promised land after forty years of wandering the desert and then passes on. One could sarcastically note that The Ten Commandments is not a legal documentary, and be absolutely correct, but that is extremely relevant to the nature of the film. It is not centered around the Law, but the human element, the emotion that film captures better than paper.

Though the Ten Commandments hog the posters and title, the giving of the Decalogue itself is saved for the end of the film, as the climax. If The Ten Commandments were an essay, this is its concluding thesis; after three hours spent exploring a non-exhaustive portrayal of Moses’ life, establishing Passover and the Exodus, it explains why you should care. Without the Decalogue at the end, the movie would not only be lacking for a title, but would have little relevance to the audience. It might be no more than the story of a tribe that escaped slavery with supernatural aid and then lived happily ever, a long time ago in a desert far, far away. The Ten Commandments themselves are the bridge from the ancient to the modern day; these are the people who followed the law, you also follow the law, therefore you may learn from their example.

This is key to DeMille specifically; his brother Richard in Michael Calabria’s The Movie Mogul, Moses and Muslims said that he was, “not a completely conventional Christian. He didn’t take directions from popes or prelates. He was more of a Protestant man of the book (Calabria 2).” If Martin Luther’s German Bible allowed the common man to learn the word of God directly, then DeMille’s film fulfills a similar, albeit reversed, role for modern American Christianity.

More and more Americans do not personally read the Bible, and are increasingly irreligious on the whole. Christianity today is predicated less on study of the Bible, and more on a pervasive common culture and understanding. Everyone knows what Christ’s message is, everyone knows what the Ten Commandments are, everyone knows what the Exodus story is, who Moses is and how he fits in. That most Americans don’t know the Ten Commandments, don’t know the particulars of early Christian doctrine and don’t know much about Moses’ background, let alone his family structure, is irrelevant. It is an informal, vernacular Christianity, modified to be compatible with a separate, secular state, and The Ten Commandments is its magnum opus. Whether DeMille understood or not at the time, the result is that the Bible itself is pushed aside as an actual source beyond common quotes. In its place, popular media that presents a summarized, modernized version of the Bible serves as an anchor, a common meeting point for a new generation of Americans, a group which contains innumerable Christian sects and increasing numbers of Jews, Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists, secular or practicing.

The focus of the film, as should now be clear, is not the Law of Moses or even the Decalogue itself, as it is not a legal documentary. It is not the ancient sources of Mosaic tradition, as it is not a biopic. To see the significance of The Ten Commandments is to look past preconceived notions of the Exodus and see what is in front of one’s nose; it is the establishment of a new, popular Christianity, inspired by but not bound by the past, built for modernity. The opening text crawl said as much; the viewers undergo the same pilgrimage as Moses and the Israelites. Through this film they are united, in the formation of a new, common faith.

Thank you, a very interesting essay.

ReplyDeleteIt has occurred to me that those parts of Raiders of the Lost Ark that aren't Harrison Ford swashbuckling or Nazi scheming have a distinct air of the Biblical epic about them: long, slow shots of desert landscapes and storm-clouds - sudden winds and flames - broad scenes with minimal human presence and little dialogue - slow, portentous music.

I'm not quite sure that this is directly from The Ten Commandments, but it would not surprise me if the visual language of the two was very close.