I just watched this video discussing the topic 'D&D Min-Max-ers Are Valid' featuring Brennan Lee Mulligan and Jasmine Bhullar. There's less discussion of the topic than I hoped, though I disliked their treatment of the topic less than I expected. Still, I think they manage to miss the point in a very juicy topic of discussion, and since I had strong opinions on the matter I have come to inflict them upon you all.

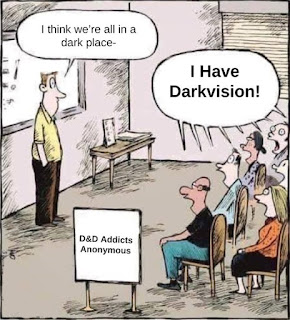

I must confess: I am a min-maxer. And I have a problem with min-maxing.

Does that not make sense? Read on.

|

| Hello, Byzantine |

Before I played TTRPGs, I played videogames, including a lot of CRPGs and single-player games. I was, and remain, a compulsive save-scummer. When I played Baldur's Gate, or Thief: The Metal Age, or Morrowind, or Hitman: Blood Money, I would be constantly saving, taking an action, failing, and trying again until I could get it exactly right.

It was not fun, but I did it anyway.

In our neck of the woods, it's not unusual to complain about the tyranny of fun, the notion that bowing to the dictates of short-term enjoyment makes long-term satisfaction very, very difficult to cultivate in a campaign. This is a related problem, I think. The satisfaction of finally getting past that one guard in the most difficult and obvious way possible after a dozen tries is short-lived, and by committing myself to that I cut myself off from many other, much more enjoyable, approaches. How many cool assassination options did I miss in Hitman, how many side paths and schemes did I miss in Thief, because I wanted to bulldoze through the game in a straight line?

It's worse in RPGs. I recently went back to Baldur's Gate to try out an evil playthrough. The first time I played it (very recently, I assure you) the first dungeon I found was actually the Ulcaster Academy. On this playthrough I decided to make a beeline for it. I was fine until I found the vampire wolf, and realized I didn't exactly have a whole lot of magic weapons that could damage it. So I save-scummed. I tried a couple dozen different times to set the fireball just right, give the rare magic weapons to the right characters and make sure nobody died. It took me a while to remember I had a dragon sorcerer and a storm cleric whose special abilities could take it down. By that point I had failed many, many times.

That experience was not strictly unenjoyable. I had some fun trying (and failing) to kill it with a fireball trap. But there was more frustration that satisfaction. I would like you to imagine the same thing playing out at a table, the players bulldozing into an encounter with a creature they cannot normally beat, and demanding a do-over each time someone dies until they can get the perfect outcome. If I had players like that I would quit GMing.

By contrast, I wrote recently here about my first time playing Ultima Underworld this past year. I went in completely blind. Others might find the experience detailed there to be undesirable, but it was a blast for me. I was immersed and engaged. I was afraid and surprised. I died a miserable death, and loved it.

The bottom line here is that many of the best experiences in gaming (video or analog) happen under conditions of sub-optimal play. Part of this is because sub-optimal play leaves space for learning and optimization, which are often enjoyable, but also because it creates room for improvisation and unexpected situations.

Back to TTRPGs.

I think games are at their most boring when they're optimized. This can be related to the creation of a meta (my best friend in high school was a relentless optimizer who tried to get me into TF2, MtG, and Realm of the Mad God by bashing my head with the meta first, no dice, many such cases), but just as often it's smaller bits of optimization like a character creation system that have a few, clear peaks.

Unlike videogames or card games, TTRPGs seem uniquely situated to prevent the dominance of meta or super-optimized tactics thanks to the GM's freedom to create new challenges and issue rulings. That's why I don't regard D&D monsters like the ear piercer as something bad. These are the footprints of an ever-evolving cat and mouse game between player and GM, but one which neither side is trying to 'win.' The GM could 'win' that fight in an instant using infinite Tiamats, but it would be totally worthless, because the enjoyment is in playing the game and the goal is to keep it going. Without GM freedom, the players could 'win' by finding the local optima and crushing whatever 'level appropriate' encounters got in their way, but that too would be hollow because there would no longer be the sense of risk, surprise, and unpredictability which made it fun. Just endless CR-balanced encounters at regular intervals allowing for rest, stretching into infinity. Perhaps we must imagine Sisyphus happy, but I think players and GMs would concur with the Greeks that this would be a curse.

But this is perhaps too harsh a treatment of optimization. It is an activity in which many people engage with enjoyment. And it should be clear that optimization and min-maxing are not quite the same behavior. Mulligan and Bhullar offer some pat responses to the issue, but it remains that min-maxing is a behavior which occurs and which many people evidently have a problem. I think they missed the subtler point, which is that min-maxing and roleplay are antagonistic to one another. This does not mean that a single player can't do both, or that a campaign cannot include both (examples to the contrary abound), but rather, that they are different activities. When one is min-maxing, one is not roleplaying.

They come from a culture of play which takes for granted that D&D (5th, pretty much exclusively) is a storytelling game. This is not an opinion I share, but it remains that many people run story-centered games using it and show no signs of stopping. It should still be clear under these premises that when min-maxing occurs, storytelling does not occur.

But we should not take this for granted.

One doesn’t often find discussions of min-maxing in games of Call of Cthulhu or Paranoia. This is in part because there’s not much to optimize in either, and in Paranoia the character creation process invites other players to screw up your character and make them a gormless idiot. But it’s also partly because optimization wouldn’t contribute much to either game. Cthulhu characters are created to die or go insane, that’s the payoff, it’s fun. Being the only gormless idiot in a party would be tiresome, but a whole group of them is hilarious and fits perfectly with the game’s comedy dystopia.

We might also consider Vampire: The Masquerade. I ran a one-shot of V5 earlier this year for my regular group, mixed results, but spent a while reading through optimizer threads about the earlier editions. Apparently the original Vampire: The Masquerade was broken in terms of character power right out of the box, with Celerity being by far the most potent physical discipline and Dominate, well, dominating pretty much everything. I get the feeling that this wasn't much of a problem during the original game's development, given that it's explicitly aimed at being a story game (before that term got more closely codified). If one is playing a game of undead ennui, I can see the horrendous balancing not coming into play much; the issue arises when people come to the game with the assumptions of tactical play and that the system exists to be optimized. Lesson: don't bolt a complex and badly balanced character creation system onto your story game.

Early D&D is arguably in the same boat as CoC and Paranoia. Stats are random and hard to change, classes don’t give you much power, spell selection is limited and semi-random, a lot of power comes from magic items whose acquisition is uncertain, etc.

Discussion of min-maxing really kicks off with AD&D 2nd edition: it’s no surprise that this is the edition which opened up point-based class customization, kits, and player-facing splatbooks, but also the one which enshrined the attitude that D&D is a storytelling game into the rulebooks. Two commercial interests, one to sell to players, especially optimizers and completionists, by expanding options for character creation, and the other to sell modules that could be commissioned and put out with a minimum of play testing (such as the Dragonlance modules, which began earlier under 1e but certainly reached the height of their influence in 2e, explicitly story-centered and horrendously railroaded products indistinguishable from the novels which they were adapted from/into) collided to create a play environment in which mechanics and world/narrative are at odds.

This is the major complaint. The issue is not, as Mulligan and Bhullar seem to think, that novice GMs have difficulty challenging powerful characters, but that when I am recruiting players I have to deal with people who ask me if I know about the 'coffeelock' (this seriously happened, I blacklisted the guy there and then). Is it not right to respond to such things with wailing and gnashing of teeth?

To be clear, the problem is not that min-maxers seek to optimize, but that they view the game mechanically first and as a world second. My job as a GM is first and foremost to present a world in which my players can act. The rules are an aid to that end. I would rather have players who understand this, and recognize that disjoints and exploits in the rules are the result of mortal error, not the nature of the fantasy world.

The problem of min-maxing is twofold. First, there are players who engage with the game primarily on the basis of system optimization. Second, the world of the game is one in which this optimization leads to dissonant outcomes.

For examples of games which both allow optimization and have a world consonant with it, we might consider superhero games. I shall neglect to expand on this point.

To ground this a bit more in the text, Bhullar makes reference to the 5th edition paladin/warlock multiclass, which is widely understood to be very powerful. It is taken for granted that this is an example of min-maxing, rather than one driven by roleplay. It is not impossible for this to be a roleplay-driven decision: I can easily imagine a paladin who loses their faith and turns to the patronage of some other being. But I would assume that this was not the case.

Does this matter? Only insomuch as character classes are something other than bundles of mechanics. If paladins are only martial characters who can cast some spells and do big damage against some creatures, and warlocks are only short-rest based casters, nothing objectionable occurs. But hopefully, a GM and their player would want these things to mean more than that. This is a fantasy roleplaying game, and perhaps the paladin class exists to facilitate the fantasy of being an oathbound knight and the warlock exists to facilitate the fantasy of being a magician bound by a pact. Both of these are excellent fantasy archetypes. It would not even be difficult to combine them. Perhaps the paladin's oath and the warlock's pact are guaranteed by the same being, who grants its servant gifts from different 'packages' as needed. Perhaps this is a fallen paladin in a world where paladin powers cannot be revoked who seeks a new benefactor. But this would be unique to a given table, and this runs contrary to the assumptions of this culture of play: because a GM who grounds this choice in flavor might, say, require a quest to obtain the favor of the patron, or may even declare that in their world, this would not make sense and hence is off limits. I can just imagine the fire, fury, and r/rpghorrorstories posts that would result.

Matt Colville has made a version of this point before, so I will reiterate it only briefly. The game design choice to separate character creation options from the flavor of the game is one which I would characterize as a failure to make mechanics and roleplay consonant. The result is a game in which the two are effectively independent, and thus a game which is not 'about' anything in particular. I have great sympathy for the GMs who complain of min-maxers, though they may not understand the root of their complaint.

An example: I've run a short Legend of the 5 Rings 4th edition campaign a couple of times now. This is a game which comes with a detailed default setting and character options which are firmly grounded within it. If I were running that game instead, and a player wished to, say, take a dip in another clan's school for a powerful synergy, my response as a GM would be immediate and clear: this does not make sense. I might permit a player to effectively betray their clan and court another to learn their techniques, which would take quite a lot of time and effort and have serious ramifications for the campaign. If they wanted to keep learning their original clan's techniques, they might have to seek out a teacher and bribe or blackmail them, or find one in exile, if one such even exists. I suspect very few players would object to my placing these obstacles in the path of the player's optimized character, since it is clear within the norms of L5R that these mechanical decisions are closely linked both to flavor and to the character's place in the world. It is one in which mechanics and roleplay are consonant.

That is the sort of game I like to run, and I think it's the sort of game many other people would like to run, if they knew it existed. To dismiss complaints of min-maxing without seriously considering their origins does a great disservice.