As written, the timescale of the adventure shortens as the level increases. The first couple chapters feature a lot of travel and will have the party facing a large number of small problems, probably split up over the course of several weeks. Then Sunblight and Destruction's Light play out in the course of a couple days, max. Auril's Abode and the Caves of Hunger are dungeons that the players will take on in the course of a few in-game days, and Ythryn is basically a pointcrawl with a few small dungeons. Anything after that is likely to feel like an extended denouement.

Chapter 6: Caves of Hunger

This section is quite solidly done all things considered.

There is one issue Justin Alexander brings up in his review: the PCs are the first people to enter the caves in a very long time, and they had to steal a scroll from Auril's basement to do it, but this is undermined by the quite substantial number of other creatures that are also here.

|

FOR THOUSANDS OF YEARS I LAY DORMANT

WHO DARES DISTURB MY SLUM-

Oh, it's you |

In fairness, the specifics of this are handled pretty well. Most of these creatures are constructs or undead that have been around for a while, the rest are mostly minions of a vampire which the PCs woke up by opening the entrance. The presence of drow mages looking to get into Ythryn is a bit too coincidental. It can be justified: maybe the presence of the duergar in the region also led the drow to pay more attention, and they dug a way in or found one as a result. But it needs to be set up a little more. I don't have many more notes on the content of this section, and didn't make substantial changes. That said, this chapter's place in the structure and pacing of the campaign needs some attention.

Campaign Structure

This is the home stretch. In all likelihood, the PCs are leaving Icewind Dale for the last time on their way to the Caves of Hunger, which lead directly to Ythryn in Chapter 7. The previous events of the campaign need to set up the climax and connect with it. Do they?

In the first two parts, the focus is on the Dale and its people. There's lots of travel, gaining renown among the survivors, and coming face to face with the effects of the long winter.

Then the duergar show up, you do a dungeoncrawl, and a substantial number of the towns and people get destroyed. At this time, the focus switches from the Dale and its people to a treasure hunt. There's little support or guidance for sticking around and helping to rebuild, or leading the survivors out of the Dale. Nor is there a sense of pressure to actually try to solve the problem of the long winter.

The players might wind up doing this by accident, by slaying Auril in her abode, or by killing her pet bird. There's a very loose sense in which exploring Ythryn can solve the winter, in that the floating city was powered by a device which could probably control the weather, and which might still be operational. However, as written, it doesn't quite do the trick. While the mythallar does exist, is functional, and can control the weather, as written it's not powerful enough to be a permanent solution (the weather controlling spell has to be recast 3x a day, might require concentration to maintain depending on how you interpret the rule, and, eyeballing the poster map, its range doesn't even seem to reach Bryn Shander).

Not to mention, from the perspective of characters in the world, this has to seem pretty far fetched. If the goal is to end the Rime, why uncover an ancient frozen city instead of taking the fight to Auril (which is far-fetched in a whole different way, but simpler in comparison).

In any case, going to Ythryn is the quickest way to solve the winter... because 24 hours after you get there Auril shows up out of nowhere and wants to fight to the death. For some reason. And if the players win, which is fairly likely, there goes the winter and the players' biggest reason to explore Ythryn.

Chapter 7: Doom of Ythryn

In my own campaign I made some substantial changes to Ythryn, mostly to make it consonant with my version of Auril's plot. I put the city in a 12-hour time loop which gradually turns the mortals who survive it into nothics. There's more details, but they're so specific to my own campaign that they're not worth hashing out here, especially because I would do it differently if I had to run it again.

More than any other part of the campaign, Ythryn needs a solid answer to 'What does Auril want?' and suffers for the vagaries of the base text. Auril is weakened and afraid that other gods will come to attack her so... she draws attention to herself by blanketing a whole region in endless winter? It doesn't quite add up. I ad-libbed an explanation dealing with Auril's daughter, the end of Dungeon of the Mad Mage, a phaerimm, and the aforementioned time loop, (how's that for a noodle incident?) but looking back on it now there's a much simpler solution.

What does Auril want? She's trying to drag Icewind Dale off the material plane and make it into a demiplane under her own control. Why do the other gods have difficulty reaching their followers? Because she's deliberately cutting off their connection. Why the endless darkness and winter? To transform the Dale into a place suited to her own divinity. You can also do some neat stuff with Auril as a tripartite goddess, a separation of herself into three parts which has weakened her, but is also necessary in order to fuse with the Dale and take control of it.

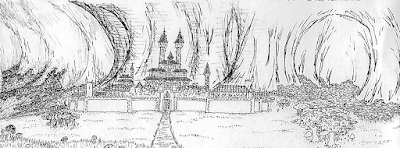

|

| Home sweet home |

If you take this route, then the role of Ythryn likewise falls into place: it's the core of the whole ritual, a fallen city which she has already basically turned into her own plane (hence also why reaching it requires the Rime, as opposed to a really big drill); it's the proof of concept for her whole scheme, and also the fulcrum on which it turns: I would make it so that the mysterious obelisk the Netherese were messing with that caused the city's fall is also the thing Auril needs to fulfill her plan.

[EDIT: These two posts were originally written and almost finished around June 2023. As I come back and finish them in November, it turns out that my post-hoc explanation for Auril's motivations is basically the same as the evil mind flayer plot in Phandelver and Below: The Shattered Obelisk. Someone owes me money.]

Now it makes sense for the PCs to come here to end the winter, and it makes sense for Auril to come here and stop them.

The other details on Ythryn are going to depend a lot on your table and other changes you've made, but it's mostly a matter of maintaining consistency.

One issue might be that Ythryn as written is both too large and too small. It's too small in that, if you look at the map and the attached scale, the whole city is... half a mile across.

Now, I've never built a magic flying city, and those who can, do, and those who can't, write blog posts. But all the same, it's really underwhelming for the city to be so tiny. But at the same time, there's a ton of stuff packed in there. Which makes sense, it used to be a city filled to the brim with mages and their crazy experiments. But in terms of pacing, it's in an awkward spot. The players will see an appreciable fraction of what the place has to offer, but then Auril shows up and... denouement.

There's a whole laundry list of things to collect in the city which ultimately lead to opening the forcefield and getting to the mythallar, but I just don't see any party getting close to collecting all of them before Auril shows up, especially because the random encounter table is going to throw about a hostile random encounter at them every other hour of exploration. Even if one can explore basically the whole city and unlock the force field in a day, that just makes Ythryn feel even smaller.

If you do defeat Auril, end the winter, and then decide you still want to explore Ythryn, great, but... where's the urgency? You can bring in some rival parties, maybe Arcane Brotherhood or some drow, but that'll feel like a huge letdown.

This is the change I would advise: first, make the city way, way larger. There's a disconnect in the mapping with the Caves of Hunger: the region map makes it look like the distance between the cave entrance and Ythryn should be several miles, but the caves as mapped are nowhere near that large. This works to our advantage. In this new continuity, Ythryn is colossal, dozens of miles across. Virtually all of that is frozen solid under the glacier, but this central section is intact and accessible thanks to the lingering power of the mythallar.

You might also split up the Caves of Hunger a bit, so some rooms are separated not by a few feet, but miles of icy caverns. Alternately, perhaps we're leaning into the Caves/Ythryn as Auril's personal domain, and it's more like an extradimensional space that the Rime is needed to access; the entrance and the city have geographical locations, but spatial relations have gotten so messy that you can cross miles in a single step.

Epilogue

The conclusion to the adventure admirably acknowledges that the ending is likely to change based on both player decision and the whims of the dice, with broad descriptions of what may come if the players defeated Auril, were defeated and allowed winter everlasting to fall on the Dale, or even transported themselves back in time to Netheril.

I have no particular insight here. My game ended early with the party destroying Ythryn and killing half their number by calling down the Ebon Star, leading to the land's subsequent takeover by Hastur. Good times.

|

Fuck that one planet in particular!

Source |

Addenda

Addendum: Tripartite Goddess

In his review, Justin Alexander

notes that the premise of Auril as a tripartite goddess (full of feyish mystery and promising really interesting interactions) was rather underutilized.

I did not make Auril a tripartite goddess in my version (my party only ever managed to destroy her first form before they fled/got killed [by their own damn foolishness and a meteor], and never saw her third), but I would recommend doing so for anyone remixing the campaign.

We can keep each 'form' pretty much as is, but now they're separate aspects, and destroying one does not transform it into another.

The first form, a giant chimera of woodland beings, is wild and animalistic. It is the boogeyman that snatches children in the night, kills livestock, lurks beyond the treeline. Rather than putting this form in any one place, put it on the wilderness encounter table. At CR 9, it's a tough cookie, but by no means insuperable even for a level 4 or 5 party: most of those wilderness encounters will be the only ones the party faces that day, and single monster encounters of a given CR are easier than equivalents with many monsters, as a general rule.

Having Auril, albeit in her weakest form, on that encounter table elevates the wilderness and gives it a nice touch: it's one thing to be big and deadly, it's another thing entirely for the bestial avatar of an evil goddess to actually stalk the land! Coming up with some situations in which the first form could be found might also be good.

Since defeating Auril permanently is likely to require defeating all three forms, this means players might not get a chance to do so just by going from dungeon to dungeon: they might instead have to be proactive, organize search parties, and hunt Auril down later in the campaign. Imagine running down an evil god on axebeaks, undead sled dogs giving chase! Now that's pulp flavor!

The second form should be on Grimskalle, and works very well with the more thorough remix of that location mentioned in the last post. This one is a frost queen, beautiful as the dawn, treacherous as the sea, whom all must love and despair! This carries the most oomph if Auril is surrounded by her devotees the frost druids. Again, this requires much more work in remixing than other changes I've mentioned, but I think it's worthwhile: of all the elements in the campaign that don't get a lot of payoff, the cult of Auril itself and the frost druids who serve it are a big lost opportunity.

Chapter 5 is big on Auril having a genius loci (basically local omniscience) of the island of Grimskalle, which I too quite like, especially if played intelligently. At the same time, she can't leave the island, and is instead focused on coordinating the frost druids and keeping up their morale, as her primary agents in the Dale. Do note that the goal of Chapter 5 has not changed: we want to get the Rime out of the basement, not kill Auril. Granted, destroying the second form is more doable than defeating all three forms, but our addition of frost druids should swing the party's chances back the other way.

The third form should be in Ythryn, hidden away inside the mythallar chamber. In addition to being a cool setpiece for the final showdown, it makes obtaining the mythallar conditional on defeating Auril and gives every party a reason to investigate the city and take down the force field, which leads them through an interesting treasure hunt with a lot of neat encounters.

It also makes more sense given our remixed motivation for Auril, but even makes more sense in the original. Whether Auril is on the run from divine enemies or trying to turn the Dale into her own demiplane, there is no better place to hide her divine spark: a powerfully magically protected magic item, whose power she can siphon to heal to heal or do whatever else she needs, hidden away for millennia under a glacier in a frozen, preserved city. Arguably moreso than Grimskalle, this is her home turf, the place that resonates with her divine essence. In any case, it should be clear that her control over the endless winter comes from the mythallar, and defeating her here ends the winter, even if her other forms remain extant.

To add some more folkloric flavor to our tripartite goddess, we might make defeating her take more than just reducing her to 0hp. Maybe the first two forms can't be destroyed in combat, instead reappearing the next 'dusk', but they can be destroyed for a year and a day under certain conditions. The bestial first form crumbles to snow if caged or otherwise restrained from dusk till 'dawn'. The second form recreates itself from the surface of Grimskalle within an hour of destruction, but is likewise destroyed for a year and a day if it is tossed into the ocean, where the hostile energies of her enemy, Umberlee the Bitch Queen (yes, that is seriously what Ed Greenwood called his evil sea goddess) unmake her. The third form, I think can be destroyed the usual way. That boss fight has enough already, no need to complicate it further.

We might also make it explicit that Auril's tripartite nature (which is apparently new to this module) is actually a ritual component of her attempt to absorb the Dale: becoming three to merge with the land and become one again.

Of course, she's still a god. Each destroyed form will return after a year and a day (perhaps they all return a year and a day after the most recent destroyed form), but if all three are destroyed before the others can return, that does something more lasting: perhaps she cannot set foot bodily upon the mortal realm until a powerful summoning is conducted, or she is at the mercy of her divine enemies.

|

Sovereign of summers lost

Source |

Addendum: Auril's Motivation

Let's collect all the things we've implied previously and put them together for clarity, laying out Auril's plan and a how it interfaces with likely player action.

In our revamp, Auril wants to turn Icewind Dale into her own demiplane by shrouding it in eternal winter, eventually blocking off escape and killing the remaining sentient beings (maybe including her own cultists, maybe not) as part of a mass blood sacrifice. By the time the campaign begins, the winter has gone on for two years, and the ability of other gods to interfere in the region is patchy (not sure how clerics are still getting their spells, in that case, but let's roll with it).

Through her cultists and frost druids, Auril has instituted a climate of fear and paranoia in the Ten Towns. They say that Auril is wroth and wants to kill them all, but her wrath may be spared with a sacrifice, chosen by lottery. These killings are doubtless secretly sanctified to the Frostmaiden (or perhaps, after two years, it's not secret at all) but it's a lie. Auril doesn't want to kill everyone yet; she just wants to keep Ten Towns in line and keep the fear and cruelty and suffering and murder at a steady, controlled simmer. This is evidenced by the continued survival of other groups like the goblins, orcs, and the Reghed tribes. They aren't making sacrifices, and they're suffering, but not nearly as badly as they ought to be if Ten Towns' condition is being bettered by sacrifices.

The Sunblight duergar were invited into the Dale by Auril under false pretenses: a sunless surface would be great for them, conditional on them being able to survive the cold, and she must have promised them some favor when it's all over. This too is a lie, as Auril just wanted more sacrifices and figured that a struggle for dwindling resources between the Ten-Towns and duergar would give the Dale's last days some extra kick, just a nice little spurt of rage and despair.

Unfortunately, she underestimated the duergar and their ability to construct colossal robot dragons. The flight of the Chardalyn Dragon blindsides everyone, including Auril and the frost druids, and both its attack and the simultaneous duergar invasion kill too many too quickly, thus galvanizing resistance and giving rise to heroes in Ten Towns, instead of continuing the slow, steady decline into helplessness and despair Auril wants.

This is probably the first time the payer characters seriously appear on Auril's radar.

Whether motivated by a treasure hunt, a search for answers, or range against Auril and her cult, seeking their headquarters in Grimskalle is a natural move that lots of PCs will do on their own, eventually. If they know from some studious source that the Rime contains the secrets of the cult's inner circle and that Auril's second form simply reforms from destruction, they will probably focus on retrieving the Rime and sabotaging whatever they can. Lady Frostkiss' genius loci over Grimskalle is still a big problem, but some thing like, say, a coalition of human and orc tribes, ten-towners, and goliaths launching a coordinated raid might just distract her long enough to heist the Rime. Or whatever other plan the PCs can come up with, it's their call.

Here's where we add another wrinkle: the Rime not only contains the teachings of her cult's inner circle, not only contains the formula to open the way to Ythryn, but contains this very plan, as outlined to the cultists and frost druids (whether she told them the truth about their own eventual death is up the GM). With this in hand, the PCs likely set out to abolish the lottery and destroy the cult's influence in Ten Towns.

Auril realizes her plan is now seriously threatened. She mobilizes her remaining followers and sends the first form to hunt down the party, but PCs being PCs it's likely not enough. Her second form is bound to Grimskalle and her third has to stay in Ythryn to control the mythallar. She steps up her timetable. The winter takes a sudden turn for the much worse and leaving becomes much, much more difficult. She wanted to smother the Dale and let it die slowly, but now a quick and dirty death will have to do.

Going to Ythryn now becomes a must. Chapters 6 and 7 play out as outlined above. Hopefully, Auril is defeated in time, the spell is broken and the Dale can begin to recover.

Within our new structure, the campaign only really needs a few assumptions about player behavior, those being:

1. The players want to fight the evil robot dragon burning down their home,

2. Want to get answers about the winter/stick it to the frost cultists,

3. Want to steal the book with said answers holy to the frost cultists from Auril's basement,

4. Want to explore a city of lost magical wonder and in so doing end the winter,

I think most parties will do all four without NPC hand-holding, not least because all of these are awesome. Now that the Rime is a source of answers about the adventure's plots and going to Ythryn is actually a reliable way to end the winter, our linear campaign structure is much more robust, with the Chapter 2 sandbox available to fill in the interludes, and proactive play is rewarded. I'll call this a good day's work.

Addendum: Wilderness Encounters

I gave the wilderness encounters short shrift in the first post, I think for good reason, but it stands that having those encounters is useful in making the wilderness feel big.

Of course, they collaborate with other elements to this end. If you want wilderness journeys to feel long without actually making them take longer at the table, your bets bet is do have them deplete resources. This is more challenging in 5e because the most important resources to the players (their daily abilities and hp) come back almost entirely after a long rest, and is made more difficult because most games don't track things like food, encumbrance, light, et cetera.

Before changing the encounters table, take steps to enforce these things. Of course, if you don't want a game with resource depletion and survival elements (my own campaign dropped these elements for expediency), then the wilderness encounters table can become a sometimes food as well.

I might advise turning it into a 1d8+1d12 table, adding a few non-hostile encounters, and having some entries pull double duty, like 10: 1:2 chwinga, 1:2 dwarves. The blizzard die can stay.

For a more ambitious remix, prepare variant encounters with higher difficulty to use either in the deeper tundra or as the winter gets worse. That peryton encounter won't challenge parties after Chapter 4, but increasing their numbers a bit and giving it some other new spin or buff can breathe some new life in and keep it fresh and challenging.

|

| Source unknown |

Addendum: The Rime

The whole module is named after a poem ('Rime' being a pun, both an archaic spelling of 'rhyme' as in 'Rime of the Ancient Mariner' and meaning frost that covers an object like a window), but the actual poem is pretty meh. The community for the module on reddit had some good alternatives, with Shelley's

The Cold Earth Slept Below being my favorite alternative.

I also edited the original to be a consistent trochaic tetrameter catalectic, reproduced below, and someone else put this version of the Rime

to music.

Bow to She who bears the Crown

Shiver all in whispered Dread

Clad in winter’s whitest Gown

Snow enshrouds the blesséd Dead

Fury sheds but frozen Tears

Wolven howling issues Forth

Wind across the wasteland Shears

Breathing blizzards from the North

Ice-kist flowers caught in Bloom

Beauty kept in perfect Place

Summer swiftly locked, Entombed,

Stilling in Her cold Embrace

All the world in winter’s White

Gossamer of sleet and Ice

Set on never-ending Night

Calls unearthly Paradise

Spy her everlasting Rime

Grace in every sparrow’s Fall

Pray that you be trapped in Time

Fill her glacial palace Halls

Sovereign of summers Lost

General of winter’s War

Long live queen of cold and Frost

May She reign Forevermore

Addendum: Dreams

I mentioned in the first post that I cut out the trials from Grimskalle, both for pacing and just because I didn't like them. However, I took some of those elements and put them earlier in the game, specifically as prophetic dreams. After the players experienced cruelty, isolation, endurance, and preservation in some significant way, I'd give one of them a dream. I still have the texts written up, and they follow.

First set of dreams

You spend the night in Dougan’s Hole. The wind howls hatefully through the Stones of Thruun. Your dreams turn toward the cold, and in a moment, you are elsewhere.

You are the shaman of the Bear Tribe. The Bear King’s third wife has come to you for help with her morning sickness. You brew her the same concoction you brewed for the last two wives, to make her and her child waste away. Perhaps the King will recognize your love for him now and take you to wife.

The snow beneath your feet vibrates, each crystal forming a note of a discordant voice. It says, “This is the virtue of **Cruelty**. Compassion makes you vulnerable. Let cruelty be the knife that keeps your enemies at bay.”

You are the shaman of the Elk tribe. The tribe trudges through a horrible blizzard. Your fingers have frozen, and with them your magic. You slaughter one of your sled dogs and warm your finger in its entrails. This is surely a punishment by the Frostmaiden. It cannot be undone. It can only be endured.

The snow beneath your feet vibrates, each crystal forming a note of a discordant voice. It says, “This is the virtue of **Endurance**. Exist as long as you can, by whatever means you can. Only by enduring can you outlast your enemies.”

You are the Queen of the Tiger Tribe. You saw your husband impaled on a mammoth’s tusk, and did not save him. His child is born to you months later. You toss her into the Sea of Moving Ice as a sacrifice to Auril. With the Frostmaiden’s blessing, you will live forever, without need of any other.

The snow beneath your feet vibrates, each crystal forming a note of a discordant voice. It says, “This is the virtue of **Isolation**. In solitude you can understand and harness your full potential. Depending on others makes you weak.”

You are a hunter of the Wolf Tribe. You struggle to raise your yurt in the dark. It’s just a few of you left now. Everyone says the Wolf Tribe will not survive even another year of the endless winter. You shield your child from the cold. You will teach her the ways of the wolf tribe. She will teach it to her children. The Tribe will remain. It must.

The snow beneath your feet vibrates, each crystal forming a note of a discordant voice. It says, “This is the virtue of **Preservation**. Every flake of snow is unique, and that which is unique must be preserved.”

You wake in a sweat, the howling of the wind loud in your ears. You return to sleep to escape the cold.

I also write up a unique dream at this stage for ht fifth player in the group, who was playing a frost druid worshiper of Auril. The bit in bold is specific to my campaign, and you should replace it with details of your own.

You stand amid an endless sea of snowy dunes under a black sky. You are not alone. You sit beside a cross-legged figure, cloven-footed, wolf-furred, with the head of an owl with curling horns. Her cloak is a frozen waterfall that moves like fabric.

She looms over a miniature city, perfect in every detail. With inhuman care, she paints and polishes over every scratch and imperfection, places figures of scrimshaw and carved ice to her fancy. She mutters a rhyme to herself as her talons work with impossible precision.

*The cold earth slept below; Above the cold sky shone; And all around; With a chilling sound; From caves of ice and fields of snow; The breath of night like death did flow; Beneath the sinking moon.*

Over her shoulder, you spy some of the figures. A red-mawed hyena. A skull. A black dwarf. A white dragon. Four wizards, one already tossed aside. Another dragon, black and half-constructed from crystal. You, and the other Giantslayers. The prize of her collection, a slug with a vicious maw of teeth, preserved inside a glass bauble at the heart of the city.

Her tune stops as she notices you looking over her shoulder. He pushes a talon between your eyes and you fly back, fly up with impossible force. You hang above the world, standing still yet furiously accelerating.

No sun, no moon, no stars. Only the luminous shape of Toril. The coastlines you know only from maps are there before your eyes. All the land is white with snow, and all the seas gleam frozen.

She catches you in her talon, now large enough to hold the world in her grasp. Her head rears back and a cry echoes forever.

EMPTY NIGHT!

This round of dreams came early in the campaign, around level 3 I think. The players got another set of dreams, these showing relevant characters who also embodied those ideals.

You are the Cub*. Your parents gave you another name, but you no longer remember it. It has been ripped from your mind. You are the Cub. It is what they called you. The monsters that slew your parents and gave you up to the abominations from beyond the stars. They have you sedated, half-awake. Your scalp has been cut away, and they prod at your brain, tearing out the memories they don’t need. You are conscious, but unmoving as one of their machines plucks out your eye, nerves and all. Then they replace it with cold metal. You’ve never known something so cold, even in the Dale. Your body rejects the implant, and they take notes. There is one thought left, and it is what you focus on, every moment of every day. The faces of your abductors, and what they would look like strangled, purple and bloated, begging for your mercy.

The vision folds and refracts, as if seen through many layers of ice, and a discordant voice radiates from within you. “This one has passed the Test of Cruelty.”

You are Dzaan, Red Wizard of Thay. You recline in an upside-down laboratory, amid the wreckage of alchemical equipment and magic runes on the walls and ceiling. You bounce a ball of light against the wall idly. Eight hundred thousand and one. Eight hundred thousand and two. Or was it three? Your servant, the wight, stands in the door outside, glaring at you. Eight hundred thousand and four. Eight hundred thousand and five. Moment by moment, you’re putting together the pieces. It all makes sense. It’d be very impressive if you could ever tell anyone about it. Maybe someone will come by and rescue you? Unlikely. Eight hundred thousand and six. Eight hundred thousand and seven.

The vision folds and refracts, as if seen through many layers of ice, and a discordant voice radiates from within you. “This one has passed the Test of Isolation.”

You are Roderick**. You rest fitfully, adjusting back to soft beds and a warm fire after four years of prison life. The mead in your blood dulls the adjustment. You don’t know what’s going to happen next. For all you know you may have been safer in prison. Will you leave the Dale? Can you? Is it really possible, as Stughok and his friends claim, to end it? You don’t know. Right now, it’s just a matter of staying alive.

The vision folds and refracts, as if seen through many layers of ice, and a discordant voice radiates from within you. “This one has passed the Test of Preservation.”

You are a survivor of Dougan’s Hole. You shamble through the snow, surrounded by less than two dozen of your fellows. Good Mead rejected you, and so you pass on to Bryn Shander, where you all beg and cry outside their gates for hours before their mercy is roused and they allow you in. Now they force you to sign on to their lottery, to forfeit yourselves to blind chance. And after great protest, you do. It can only take one of you this moon. You wonder what mighty force could have brought the dragon’s destruction on your people.

The vision folds and refracts, as if seen through many layers of ice, and a discordant voice radiates from within you. “This one has passed the Test of Endurance.”

*The Cub is the yeti cub from Kelvin's Cairn, which the party 'adopted' and held captive after killing its parents (evil party!), before eventually selling it to their squidling allies after the Id Ascendant was repaired and returned to the Far Realms.

**Roderick is an NPC created from the rogue PC Stughok's custom secret I made, reproduced below. This dream occurred after the party rescued him from prison and put him in Bryn Shander.

New Secret

Jailbreaker: A friend took the fall for a crime I committed. A bad one. They were sent to Revel’s End, a high-security prison in the Dale controlled by the Lords of Waterdeep. I’m getting them out if it's the last thing I do.

And that's about it! Most of the remix was written months ago, but the addenda came about in about a day (during which I really ought to be doing other things), and it was a blitz. All said, it's nice to have it posted.

If this post interested you, comment below, share it around, and subscribe to the blog. Until next time, have an excellent week.